Here’s a very technical description of how DNS allows the Internet to function:

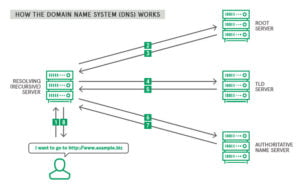

If a customer is trying to access your website and types in your address – for this example, we’ll say it’s www.example.biz – the browser and operating system quickly perform an internal audit to see if that computer has recently visited your website (IP address), and therefore has that website address in its cache (memory). If the customer has visited your website, then the answer is yes, and the system quickly recalls and displays your website without going through any additional steps. However, if it’s the customer’s first visit to your website, when the browser asks the operating system if it knows how to access www.example.biz, then the answer will be no, and the customer’s computer will then ask a preconfigured recursive DNS server to track down and provide the current IP address for your website.

Following the same logic, the recursive server – usually managed by the customer’s Internet service provider (ISP) – will then look in its cache to see if it has your website information still stored (DNS entries expire after a certain time in order to make sure that information is always current). If the answer is yes, then the recursive server will provide that answer to your operating system and browser, and your customer will now connect to your site.

The recursive server will then ask your DNS server what the IP address is for www.example.biz, and your DNS server will now provide the location and IP address for www.example.biz to the customer’s operating system and browser. The browser puts your website in front of the person who was looking for it and the process is done.

DNS Security

Despite serving as an indispensable component of the Internet, the structure and management of DNS remains archaic and cumbersome. The most common software application used to manage DNS is BIND, or Berkeley Internet Name Domain. Developed at the University of California at Berkeley in 1983, BIND still accounts for the vast majority of global name server implementations. Over the years, BIND has undergone a number of changes, with major revisions taking the code base from BIND version 4 to BIND version 8, and currently BIND version 9. But in terms of security, BIND is nothing more than attempting to apply a piece of gauze to a substantial wound. In fact, BIND is one of the all-time most common programs to be identified in the global notification system of vulnerabilities, known as CVE or Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures. And since it’s the first step in the process of device-to-device communication, DNS often serves as an easy point of attack. Here are two of the most common assaults launched against DNS:

1 Cache Poisoning/ DNS Spoofing Cache poisoning, also known as DNS spoofing, occurs when an attacker gains control of a DNS server and changes the IP address of a website so the DNS points to the IP address run by the attacker. When users try to access what they thought was the organization’s website, they are redirected to the attacker’s site, and thanks to recursive DNS, their system will cache the IP address to the malicious site. Cache poisoning can wreak havoc on a brand’s reputation and trust if wouldbe users are continually pointed towards corrupt sites that steal their sensitive information.

2 Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Attacks During a DDoS attack, a number of devices are compromised and organized to form “botnets” that are synchronized to attack a resource with such an overwhelming flood of illegitimate traffic that the bandwidth available to the victim server[s] is overwhelmed and a lot of legitimate traffic fails to “get through.” In a DNS DDoS attack, it can be difficult to filter out the illegitimate traffic because it is often composed of valid queries from bogus sources that are indistinguishable from valid DNS queries from real sources. DDoS attacks on the DNS can have a devastating effect on companies that rely on a continuous digital presence, such as streaming services, online businesses, and banks. In a relatively recent development, DDoS attacks have been used as a “smokescreen,” or diversionary tactic to keep the IT team busy while the attacker plants malware or exfiltrates sensitive information. Since DDoS attacks can be launched for as little as the price of lunch, they’re becoming increasingly popular – and devastating.

Digging Deeper: Examining DDoS Attacks Aimed at DNS

DDoS attacks have been in existence since the 1990’s, but with the rapid proliferation of connected devices and the world’s dependency on the Internet, DDoS attacks are quickly gaining space in the public consciousness. It used to be that the primary driver behind DDoS attacks was direct or indirect public recognition, but recently the motives have ranged from seeking a financial gain, to a sinister desire to influence the world. Initially, DDoS attacks were aimed at exploiting applications in general. But when attackers realized that they could cripple an organization by attacking their DNS with large packet floods, it soon became open season on all websites – and their infrastructures – regardless of how much the organization invested in network defenses. Shortly thereafter, companies began to use antiDDoS services that provided additional bandwidth and resources should they come under a DDoS attack for their Internet-facing assets. And although this method seemed to work for awhile, the public’s desire to live in an increasingly Internet-connected world took hold and gave rise to another inadvertent insecure weapon – the Internet of Things (IoT).

Impact of DNS Outage

The mere thought of a sustained, widespread Internet outage is one that would immediately send the global economy into a tailspin and grind productivity to a halt. And yet, we’ve come close on multiple occasions. On July 8, 2015, the New York Stock Exchange was forced to shut down for approximately four hours due to an outage that was caused by a “configuration problem.3” Although U.S. stocks finished down by roughly 1.5%, the scare jilted foreign markets, causing a steep decline in the Chinese markets, and raising concerns in European markets. And while this outage was not the result of a cyberattack, this example illuminates the fate of the global economy should a DNS outage occur. The Internet community dodged a bullet on July 8, but that luck would soon run out. On October 21, 2016, the world suffered one of the largest DDoS attacks ever assembled4. The assault, which struck a managed DNS provider in phases, manipulated and enlisted insecure IoT devices as part of a major botnet. Harnessing the power of the IoT botnet, initial reports indicate that the size of the attack was more than 1 terabit per second and collectively caused intermittent outages throughout the day5.

How the DNS Shield Network Learned from the Traditional Telephone System

When Alexander Graham Bell made his first telephone call, he had no awareness of its impact on the world. And he certainly wasn’t thinking about security when he yelled those immortal words; “Mr. Watson, come here. I need you.” But as the telephone systems evolved over the years, the issue of security did raise its head. And in 1975, the providers came to realize that the key pieces of completing a phone call — things like authentication which would be necessary for billing — would have to be done on a separate network to the actual circuits that carried the call.

Leave a Reply